Preface

I don’t know about you, but I’ve been dreaming of having my own signature instrument ever since my first days of learning how to play the guitar. I don’t mean “signature” in the sense of a commercial collaboration with a large manufacturer where I sign my name on a model so that they can sell more of it; I mean “signature” as in made to my exact specifications, with every little detail being the way I prefer.

Luckily, an electric guitar or bass being basically a plank with some strings on it, it’s very easy to swap little pieces out and, piece by piece, get closer to that dream of having a completely personalized instrument. I’ll try to write down virtually everything I know about guitar parts in this guide, and boy does guitar hardware have a lot of quirks and details.

Let’s get on your Road To A Signature Guitar.

Getting The Instrument

If you don’t already have an instrument that you plan to mod the hell out of, you’ll need to get one.

On Kits

I’m not a fan of overpaying for gear; manufacturing technology has reached the point where even cheap guitars — Squier, Cort, lower-end Ibanez models — are usually really good. Having said that, not even the best setup and components in the world could make some of the really bad guitars out there enjoyable to play. I would recommend staying away from the lowest-end lines of most manufacturers (Squier Bullets and Affinities immediately come to mind; the low-end lines are usually fine, it’s the absolute lowest-end you need to be wary of) and from DIY kits.

It may seem like a DIY kit is the perfect way to get a guitar that is truly yours, but most the kits out there are absolutely abysmal in quality, with misplaced and mis-measured holes for mounting hardware, neck pockets that either don’t fit the neck or only vaguely contact the neck wood at all, the absolute worst quality hardware anyone produces (often reusing parts that failed the quality assurance process and couldn’t be used for an actual instrument); they require a tremendous investment of time and money to build into anything resembling an instrument (the finish is, imo, the most tedious, time-consuming, and one of the costlier part of making an instrument), and most luthiers won’t touch kit guitars because there’s nothing less pleasant than fixing someone else’s mistakes, much less fixing both your- and the kit manufacturer’s mistakes. Buy a kit if you want to build a kit and don’t necessarily require the end result to be enjoyable to play. Don’t buy a kit if you want a good instrument.

Partscasters

DIY kits may generally be awful, but “Partscasters” are often a tremendous way to get a great guitar. You can easily find brand new or secondhand Fender necks and bodies online, and building a Strat or Tele from parts can often result in a nicer and more personal instrument than what you’d get for the same money if you bought a complete guitar.

Fender neck compatibility

Tele and Strat necks have the same width and sit at the same distance from the bridge, but have different-shaped heels — the Strat has a rounded heel that rounds the corners of the Tele’s square heel.

For this reason, a Strat neck will fit in a Tele body (although it will leave a gap at the end of the heel), but a Tele neck will not fit in a Strat body.

Jazz and Precision bass necks are interchangeable.

StewMac have a very detailed guide on building a partscaster.

Shopping for Complete Guitars

If you don’t have a guitar that you plan to mod already, and you’re not building a partscaster, you’ll need to buy a new instrument. There are a couple things to keep in mind when buying a project guitar:

- Make sure the guitar plays nicely out of the box, has a solid fret job, the wood and finish are nice. Changing the frets and finish is very costly, difficult, and time-consuming so you probably want to avoid it if possible.

- To make it easier for yourself, find a guitar that has all the routing necessary for whatever mods you want to do. If you plan to put in humbuckers, it’s easier to buy a guitar that comes with humbuckers already. If you want to put an active preamp into your bass, you might want to look for a bass that already has a battery box and enough potentiometer holes for your preamp to fit.

- If buying a hollowbody as a project guitar, try to find one that has a removable control plate on the back. A lot of hollowbodies have solid backs and the electronics have to be put in through the F-holes, which makes mods after the fact extremely annoying and difficult.

- Keeping to standard designs (Strats, Teles, Les Pauls, Jazz/Precision basses) will make it a lot easier to find replacement hardware. In the component-specific sections of this guide I will run through the standard variants of each piece of hardware and how to recognize them — a lot of designs, even if they’re non standard, will use standard hardware. Do your research; make sure you’ll be able to find a replacement bridge before you buy a guitar planning to replace the bridge.

Now, shopping.

Make a list of the features you’d like, starting with the most important to you and ending with the least important. Such a list might contain points like:

- Body shape (e.g. singlecut, LP-style, offset, semihollow, telecaster, strat; contoured heel, etc.)

- Body wood (ash/alder/poplar/mahogany)

- Brand (Squier, Fender, Ibanez, Gibson, Cort, etc)

- Bridge (hardtail, jazzmaster trem, strat trem, floyd rose, bigsby)

- Color (yellow/natural/white/sunburst)

- Control layout (1V1T, 2V2T, 1V2T, push-pulls for switching, 3-position toggle vs 5-position blade switch, etc.)

- Active electronics (yes/no)

- Fretboard wood (maple/rosewood/ebony)

- Fret count (20, 21, 22, 24)

- Fret material (nickel, stainless steel)

- Hardware color (nickel, chrome, gold, black)

- Headstock angle (straight, angled, headless)

- Inlays (dot, block; black, white acrylic, mother of pearl)

- Neck mounting system (bolt-on/set-in/neck-thru)

- Neck profile (C, D, V, etc)

- Number of strings (mainly relevant to bass: four, five; on guitar: six, seven)

- Pickup brand (Seymour Duncan, Fender, Fishman Fluence, Bare Knuckle, etc)

- Pickup configuration (e.g. HH, SSS, SS (tele), PJ (bass), P90/P90)

- Scale length (guitar: 24 3/4“/25.5“/multiscale; bass: 34“/35“/multiscale)

- Truss rod style (bullet, vintage bottom-of-heel access, Music Man-style)

- Tuners (traditional, locking)

- Weight (e.g. sub-7lbs)

Now that you have your list ready, make a copy and remove the points that can be easily changed in the future (i.e. without sanding down the finish or woodworking). That will be your shopping list.

Go to your preferred online music store (I’m a big fan of Thomann in Europe; Sweetwater in the US also have a very nice selection of guitars), click on the appropriate filters, and go through all the guitars that match what you’re looking for at least in part. Write down those that have a price that doesn’t make you flinch.

Chances are, you’ll find plenty of instruments that work for you.

Be Opinionated!

The beautiful thing about instruments is that they’re equal parts tools, commercial products, fashion accessories, and works of art. When buying, building, or modifying an instrument, it’s important to acknowledge all those aspects and use them to evaluate what you’re aiming for.

There is an entire universe of variations on and approaches to every detail of the guitar, no matter how minor. Even tuner buttons can be found in a variety of styles, colors, and materials.

Don’t get me started on tone woods — alder, ash, swamp ash, mahogany, poplar, basswood… How are you supposed to choose when there are this many options, and little to no way of evaluating them objectively?

Be opinionated.

Make up your opinions out of thin air.

Sometimes it’s viable to evaluate all the choices and list their advantages and shortcomings — e.g. locking tuners are pretty much always preferable to non-locking ones — but most of the time, that’s not an option. In those cases, follow your gut.

I strongly recommend, in those cases, making up preferences purely based on vibes. It’s not only perfectly valid, but generally leads to greater satisfaction with your instrument.

Don’t have a preference for tone wood? Look at all the options and pick the one you like best based on how it looks, or the vibe it has in your head, or even based on how much you like the name!

Mahogany, to me, sounds like a wood that’s warm and rich and makes me think of lovingly hand-crafted instruments, so I like instruments that use it.

Is that a rational opinion? Is it based on any research, factual analysis, or experience? No! But it helps me choose, and it helps me love an instrument more if it uses mahogany.

Do things that help you love your instruments. Invent silly opinions.

Guitar-related decisionmaking is driven 80–90% by pure vibes. People love or hate design decisions and components because they either vibe with them or not. The remaining fraction of the reasons for a decision is split between feel (i.e. how well something works for your personal style, technique, anatomy, or even visual taste) and rational evaluation (i.e. comparing the pros and cons of various options).

Hop onto any guitar forum and you’ll see this principle in practice, although often thinly disguised under the pretense of “tone” or “sustain”. You’ll find hordes of people on Tele forums swearing that there’s nothing better than the vintage tele bridge — although objectively worse than compensated saddles, and arguably strictly worse than six-saddle bridges — because it gets the “best tone”; hell, I’ve even seen claims that vintage Kluson tuners improve the tone of a guitar while writing this book.

This is all bullshit, of course. It’s code speak for “I have a preference for this particular component that I cannot justify through rational means”. And you know what? That’s fine! Not only is it fine, I encourage it. Just don’t go start flamewars on forums about it, and try to steer clear of making claims about “tone” unless you’re talking about pickups (and mayyyyybe strings).

So, once again: be opinionated. Follow your gut, make choices based on the subtlest vibes. Pick one guitar over another because you like the pickup covers better. Pick a guitar over another because it comes in a prettier color. Form arbitrary preferences and act on them.

If you do this, you will not only have an easier time choosing — you’ll also end up with an instrument you love more, and you’ll run into plenty of opportunities to try stuff out and help inform the more rational opinions.

When it comes to instruments, however, the irrational opinions are just as important as valid as the rational ones.

💙

Acquiring And Installing Gear

Before we start talking about swapping stuff on your guitar for other stuff, it helps to know where and what other stuff to get. I’ll also quickly run through tools but try not to give specific recommendations because I don’t want to get into tool discourse.

Tools, or “How Do I Actually Install This Thing?”

Every hardware upgrade or swap will fall into one of a few categories, based on the tooling necessary to achieve it. I will run through them quickly and suggest additional equipment that might make your job easier.

Hope you have a screwdriver!

For virtually all of these, you will need at least a screwdriver. I will assume you have an appropriate screwdriver for any screw you may encounter, and will not mention screwdrivers when listing requirements from this point onwards. If you do not have a set of screwdrivers, I highly recommend getting e.g. an iFixit driver kit or anything similar.

-

“It Just Goes On” This is stuff like knobs, strap buttons, pickguards (sometimes), string trees, some tuners, etc etc etc, where it’s held on by friction or a couple screws. If I don’t mention tools when talking about a piece of hardware, that probably means it falls into this category.

-

“A Soldering Iron” Pickups, jacks, switches — anything that’s wired up, you will need to desolder to replace and solder back together afterwards.

I cannot overstate the utility of a good soldering iron — use a chisel tip, and the hotter it gets, the better.

Also, use leaded solder — although “leaded” sounds scary, the lead-free solder is more expensive, is an absolute pain to work with, and doesn’t actually make a difference to your health (disclaimer: am not a doctor, this is not medical advice, don’t sue me if you decide to snort leaded solder) because the boiling point of lead is far above the temperature of soldering irons, so the smoke from soldering is not lead but toxic flux fumes which are equally present in both types of solder.

Speaking of toxic flux fumes, if you’re soldering, please do so in a well-ventilated area. Worst case, just pop a window open as far as it will go, solder everything up, and vacate the room after you’re done. Other than solder and a soldering iron, a third hand is often a tremendous help. Third hands are cheap and basically all the same, just preferably get one with gooseneck arms; the ones with solid, jointed arms can be hard to get into the right position.

A multimeter with a continuity tester is extremely useful for double-checking that the connections you make are solid, and there’s no connection between anything that shouldn’t be connected. It’s also useful to measure pots and pickups sometimes when trying to troubleshoot a broken circuit.

For neatness, I also suggest having handy multiple colors of wire if you ever need to splice some in, some heatshrink, and electrical tape. Copper tape might also come in handy if you ever need to fix some shielding, or decide to do the Fox Bridge Grounding Fix:

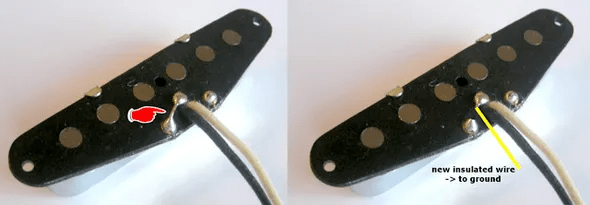

The Fox Bridge Grounding Fix

The Fox Bridge Grounding Fix is a mod I always do the first time I’m messing with a guitar.

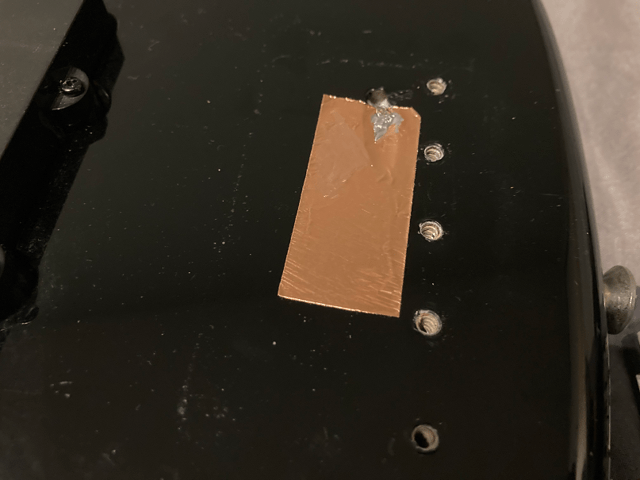

A bit of copper

tape under the bridge, with a ground wire spot-soldered on.

A bit of copper

tape under the bridge, with a ground wire spot-soldered on. Unfortunately, most manufacturers only run an extremely thin ground wire to the bridge and rely entirely on pressure to hold it there; that wire can easily become dislodged and make the guitar noisy as all hell. I’ve played gigs where I’ve had to twist an aluminium sandwich wrapper up and lodge it between the bridge and output jack to fix the noise from a grounding wire that came loose mid-show!

On voltage and grounding

Voltage is the difference in electric potential between two points — saying one point is at 1.5V is meaningless without a reference point. For that reason, one “end” of a circuit must be connected to “ground”, i.e. a reference point that can absorb lots of electricity without changing its electrical potential.

In most guitars, the ground is connected to the bridge, which contacts the strings and in turn grounds the entire circuit through the strings to the player’s body. This means that if the contact is poor or the connection to the bridge breaks, the circuit’s reference point will lose its “stability” and the guitar will become much more susceptible to noise.

I have a simple solution: the first time I take the strings off a new guitar, I always unscrew the bridge and stick a little square of copper tape underneath it, then solder the grounding wire to it. The copper tape ensures excellent conductivity and a large contact area, and the solder joint makes sure the wire will never come loose.

There’s two categories of tooling left, and those are the two I will only gloss over in this guide.

-

“A Paint Booth”

Some visual alterations, like adding decals on a headstock or painting patterns onto the body, will require you to refinish at least part of the guitar.

You can paint a guitar at home. I’ve done it. Would I recommend doing it? Fuck no.

First of all, unless you have a balcony, garage, or garden that you can afford to splatter in paint, you cannot paint a guitar safely. Paint fumes are extremely toxic and you need an extremely well-ventilated area and respiratory protection at the very minimum.

The problem with well-ventilated areas is… they’re well-ventilated. If you’re painting in a garage or a garden, you will end up with tons of plant pollen, seeds, other floaty plant bits, dust, debris, insects, and all that stuff embedded in your finish. You can get around some of it by building yourself a little paint booth with forced exhaust (I built one out of cardboard boxes and used an array of computer fans to pull air and dust out), but you’ll still end up needing to sand down every couple layers because a mosquito got stuck in the clearcoat. It takes weeks, and then the sheer amount of scrubbing and sanding necessary to get the finish to be smooth and glossy and polished will absolutely destroy your arms.

Just, don’t. It’s not worth it.

-

“A Woodworking Shop”

Take it to a luthier. Some of the more extreme mods will require you to drill or route out significant amounts of wood from your guitar. Want to replace a single coil pickup with a humbucker? You’ll probably1 need to do some woodworking — or, I would suggest, have someone else do the woodworking.

1Some Telecaster bodies are routed for humbuckers under the pickguard, even though they come with single coils.

Where To Buy Hardware From

We’re going to be talking about guitar hardware, so I would suggest finding a guitar hardware store that carries a broad range of parts at good prices and with good shipping times. If you’re in the US, stewmac is great but they kinda just carry a few items from each category. There are probably retailers with a wider selection of gear.

If you’re in Europe, Thomann is very hard to beat, although for very specialized things you might have to look elsewhere. They’re improving year by year, though — they used to have a very small selection of e.g. pickups, and now they carry pretty much everything I’m interested in.

If you’re looking for novelty hardware — knobs, pickguards, etc with cool patterns or made of funky materials — spend some time searching Reverb, Etsy, Ebay, and Amazon. Chances are you’ll find what you’re looking for; if not, googling for e.g. “custom pickguards” should bring up plenty of craftspeople who will happily make what you want.

Who To Buy Hardware From

Like with most things, there are dozens of hardware manufacturers that make products at every price point, and it can be tricky to choose if you’re not already familiar with their offerings.

My recommendations, in descending order of price:

- Hipshot (USA) — Very pricy. They make some of the highest-quality bridges you can get, excellent tuners (especially their bass tuners are somewhat of an industry standard in basses with high-end hardware), and some funky specialty hardware like detuners (under the X-Tender name) and B-benders.

- Graph-tech (Canada) — Very pricy. They mainly make nuts, but also piezo bridge systems and saddles made out of specialty engineered materials. They also make tuners.

- ABM (Germany) — Pricy. They mainly make bridges; usually out of very high quality brass.

- Schaller (Germany) — Very high quality, but still somewhat reasonably priced. They make virtually everything, from bridges, through tuners, to switches and knobs. Always superbly machined, usually using premium materials (brass, aluminium, titanium). Their straplocks are also pretty much the industry standard.

- Gotoh (Japan) — My preferred supplier of guitar hardware. Not only do they make virtually everything and at reasonable prices, but they also have an extremely wide selection of colors, styles, and materials for their products. I also appreciate that unlike most other manufacturers, they prominently list the materials used in their products — so you have the luxury of making an informed choice when you try to decide between e.g. steel, brass, or titanium saddles.

- Göldo (Germany) — They make everything, pretty cheap, and generally pretty good. Not much else I can say here. I often reach to Göldo for minor hardware that doesn’t affect playability. Göldo owns Duesenberg, btw.

- Allparts (USA, but I’d be shocked if their hardware is not made in China at those prices) — Affordable! They also make virtually everything. Hardware is good quality with solid materials.

Honorable mentions:

- Fender (USA, but hardware generally made in China) — Fender designs are so standard and so widely copied that sometimes the best way to ensure you have something that fits is to go directly to the source. Fender stuff ranges from overpriced as hell to pretty reasonable, and the quality is also all over the place, so make sure to read reviews and make a decision for yourself.

What Can I Swap Out, Exactly?

It’s hard to make informed decisions about whether you can make a guitar into your dream instrument by swapping parts if you don’t know what parts can be swapped. Let’s start from the bottom end of the guitar and make our way towards the headstock.

On the effects of hardware on tone

In theory, pretty much anything you do to your guitar can impact its tone. An instrument is a very complex physical system and changing any parameter of it will have a non-zero effect on the behavior of the system as a whole. Especially for parts that interact with the strings — the bridge, nut, etc — it’s not unreasonable to expect swapping them out to change the way a guitar sounds.

I will not talk about the effect of hardware on tone. It’s extremely subjective, and there’s no consensus or evidence that it matters at all. I will discuss the way electronics influence tone, since that part is known and measureable and described by a variety of well-understood physical equations. I will not discuss the way e.g. different materials or types of bridges can or can’t change your sound.

Strap Pins

Yes! Even the humble strap pin is potentially upgradeable.

On the importance of strap pins

If you play standing, your strap pin is all that stands between a great performance and making a guitar-shaped dent in your floor. It’s much more important to both your comfort and your guitar’s safety than it might seem at first!

There are a number of reasons why one might consider replacing the strap pins on their guitar:

- Switching to a different color for aesthetic reasons (e.g. replacing a chrome strap pin with a black one)

- Switching to a different design for aesthetic reasons or to minimize strap slippage (e.g. switching from a V-shaped pin to a T-shaped one)

- Upgrading to strap locks to entirely remove the risk of the strap coming loose

- Relocating the strap pin to improve the balance of the instrument (e.g. moving it from the back of the body to the upper horn on some SG-style guitars)

Let’s talk about all the different kinds of strap pins.

A strap pin is very simple in construction — it’s a piece of (usually) metal, attached to the guitar body with a simple screw with a (usually felt) washer between the pin and the body to avoid damaging the finish. Strap pins come in all kinds of shapes and sizes — from the classic V-shape all the way to novelty designs like skulls and stars — and in all finishes and materials, from classic nickel to buffalo horn.

Strap Pins Of All Shapes And Sizes

Almost all guitars will come stock with the — frankly, subpar — V-shaped strap pins (pictured to the right).

Honestly, I hate this design. As you can clearly see, there is very little holding the strap in place, and heavier guitars or basses will readily come crashing to the floor if the strap slips.

Luckily, there are plenty of variations on this standard formula.

Fox’s Gear: Gotoh EP-B3 oversize strap pins

My personal favorite by far is Gotoh’s EP-B3 style of strap pin, once again visible on the right.

They’re significantly oversized compared to a classic V-shape pin and have a “T” rather than a “V” profile, making them much more resistant to strap slippage. I also think they look great; they look big and unique and, especially if your hardware contrasts with the color of your guitar’s finish, can stand out in a very positively striking way. Check them out on the FGN Iliad, below:

> The FGN Iliad JIL2ASHM, with oversize Gotoh EP-B3 strap pins.

Every hardware manufacturer and their mom have a bunch of minor variations on the basic strap pin. Gotoh, for instance, other than the oversized-T EP-B3 mentioned above, also make a standard V-shape EP-B2 and a standard-size T-shape EP-B1.

D’Addario makes strap pins with an elliptical profile, which seems like a great solution for strap retention, but I happen to dislike the way they look. Pictured on the right:

There are innumerable variations on these few designs, but there are also two other significant categories of strap pins: novelty designs and strap locks.

Let’s talk about novelty strap pins.

Since a strap pin is just a piece of metal with a screw, it turns out that anything you can attach a screw to can be a strap pin with the right attitude!

Grover is the only “big” hardware manufacturer I know of to make novelty strap pins. They have a small selection of designs, including classics like skulls or stars.

For anything else, you’ll probably have to look to Etsy, Reverb, Amazon, or Ebay. Strap pins are the one piece of hardware where I would even suggest looking to Aliexpress, but I couldn’t find any novelty pins on there. I did find some nice ones on Ebay, though.

Now that we’ve looked at all the different kinds of “standard” strap pins, let’s talk about strap locks.

Strap Blocks, Strap Locks

What’s a strap lock, anyway?

A “strap lock” is any solution that goes over your strap once you’ve secured it onto the strap pin and locks it in place.

If the strap pin is not sufficient for keeping your strap secure — and, let’s face it, it almost never is — it’s time to look for straplocks.

Depending on the design, the chance of your strap coming loose if you have a straplock on ranges from “basically impossible” to “mechanically impossible”.

Let’s start with my favorite, the zero-cost solution that requires no modification to the guitar, does not make the strap pin any more bulky, and can serve as a nice colorful accent: the “Blues Straplock”.

If you’re of drinking age, Grolsch beer comes in a fancy flip top bottle with a rubber seal on the cap. With a bit of effort, you can get the seal off the cap, pull it over the top of your strap and pin, and have a very secure and near-zero-cost solution that will keep the strap in place:

The “Blues

Straplock”.

The “Blues

Straplock”.

If you’re not of drinking age, the rubber seals can be ordered in bulk from Amazon or any homebrewing supplier for dirt cheap; google for “Grolsch gaskets pack”. These are such a classic that a couple guitar companies even sell branded versions in a variety of colors for a couple bucks (the Fender ones pictured on the right)!

“Proper” strap locks, on the other hand, are something quite significantly different, but they all broadly follow the same idea — rather than having a one-piece pin that your strap is pulled over the top of, and held in place with gravity, friction, and prayers, a strap lock adds a second mechanical part that is then secured over the top of the strap, preventing it from coming loose.

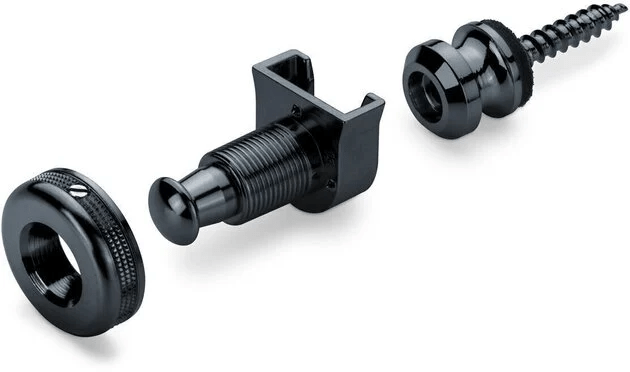

The industry standard (to the point that some manufacturers, like Ibanez, are now including them as a standard feature on some of their guitars!), and the example I will use to explain how a strap lock works, is Schaller’s S-Lock system:

The Schaller S-Lock System.

The Schaller S-Lock System.

With Schaller S-Locks, you “clamp” the strap between the lock wheel (the round part with a threaded hole) and the lock body (the long threaded part); when you want to attach the strap to the guitar, you pull on the pin at the end of the lock body (which retracts an internal bolt that locks into the hole at the end of the strap button itself) and slide the whole assembly over the strap button.

Conversely, to detach the strap, you pull on the pin and slide the lock+strap+wheel assembly off the strap button.

This arrangement makes it mechanically impossible for the strap to come loose unless you pull on the lock pin.

A strap attached to a guitar with

a Schaller S-Lock.

A strap attached to a guitar with

a Schaller S-Lock.

Virtually all other strap locks work on the same principle — the exact locking and unlocking method may differ, but they’re all some form of mechanism that slides over the strap button and locks in place.

Although they’re all kinda the same, there are two strap locks that I’d like to give a special shoutout to:

- Fender Infinity Strap Locks, because they come in a pretty sick metallic red:

- Dunlop Flush Mount Straploks, because they’re unique in that they don’t stick out massively from your guitar. On the other hand, this is because they mount into the body, and thus require you to drill a big hole into your guitar:

On that last note, I don’t like strap locks precisely because almost all the designs out there stick out a mile and look extremely gamer, and some of the pointier designs (Schaller) make it actively painful to play in a classical position because they will stab your thigh. Having said that, that’s just my personal take, and by all means, if you struggle with strap retention or want your guitar to be as gamer as possible — look into strap locks.

The Output Jack

It’s an output jack!

Please, for the love of all that is holy, DON’T call it an “input jack”.

Your guitar is outputting signal. If you input signal into a guitar, nothing will happen. Your amp has an input jack. Your guitar has an output jack.

A nice, “bare” Switchcraft

jack.

A nice, “bare” Switchcraft

jack.

There is… very little reason to ever swap out your jack, unless it’s broken.

Having said that, I hate barrel jacks with a passion — they just feel bad to plug into, and fail regularly - and I will always happily replace them with a nice non-barrel (“bare”) Switchcraft. If you have active electronics, make sure to use a stereo (TRS) jack — the third contact is used to turn the electronics off to stop your battery from dying when the guitar is unplugged.

Common output jack mounts

On the other hand, you may very well find yourself wanting to swap out the jack panel. There are a few different kinds of these, but they’re mostly standard:

- Barrel jacks will sit in a 1/2“ hole and be mounted flush with the wood, or sometimes even countersunk or counterbored (as Ibanez often does); these have no jack panel to speak of and there’s nothing you can do with them except rue being stuck with a barrel jack.

- A lot of guitars, especially superstrats, use standard “football” style jack plates. You can get these in a variety of colors and with a recessed or flush jack mount. These generally cover a hole between 3/4“ and 7/8“ in diameter.

- Thicker body styles (Les Pauls, some Telecasters) may opt for a square plate. Les Pauls use a perfectly square one, most other brands will use a rectangular plate. Measure before ordering! These, again, are available in a variety of colors and with a recess for the jack or flat, and will cover a hole between 3/4“ and 7/8“.

- Stratocasters use a funky “ferrule” to mount a standard “bare” jack. These are standard across strats and available in many colors, but be careful when ordering a ferrule for similar but non-Fender guitars — e.g. the Ibanez Talman line, although it looks like it uses a very similar ferrule, will not fit a Strat jack ferrule.

-

Telecaster jack cups

Telecasters, especially the vintage ones, use an abysmal “cup” for mounting the jack. That thing is a disaster, and a mistake on every level. Get rid of it as soon as you can. It sucks.

Why does it suck so much? As is usually the case with Fender, because of aggressive cost-cutting at every corner. The tele “cup” is a flimsy piece of the cheapest scrap “metal” Fender had available held in place with a tiny clip with about the same strength and durability as the spring in a ball-point pen.

These universally start rattling around and eventually come loose after a couple plugs–unplugs. They’re also a pain to remove. It’s like they were invented by Satan just to be the biggest pain in the ass imaginable. They’re so bad StewMac suggests periodically replacing the clip and rebuilding the inner wall of the jack hole with epoxy and sawdust as a way of preserving the original look while fixing the wobble. Nope.

Luckily, as is also usually the case with Fender, someone else fixed their mistakes! You can drop in an Electrosocket-style jack plate, a much more substantial piece of metal that mounts with two screws rather than a flimsy clip. These are inexpensive and work flawlessly. There is a bit of an art to removing the vintage “cup“s, so I would recommend looking up a video on how to do it.

Visual Mods: Minor Hardware

Visual mods are perhaps the coolest way to make a guitar truly feel special and one-of-a-kind. While it’s true that basically all of the things I talk about in this book technically do change the appearance of your guitar, I want to talk specifically about the mods that have no functional purpose in this section; the things that are “just for looks”.

One aspect I will not talk about in detail is stickerbombing and repainting your instrument — refinishing is a complicated, difficult, and expensive operation that could have an entire book devoted to itself alone; stickers are basically self-explanatory.

Headstock decals

Decals are a bit more complex to apply and generally will need a coat of clear paint over them for protection anyway, so I won’t talk about them in-depth either.

In the guitar world, there is one particular flavor of decal that needs special mention, though - headstock decals.

Yes, you can buy bootleg “Fender” or “Gibson” logos to put on your headstock. You probably shouldn’t, though, except maybe ironically on a guitar that clearly isn’t one. These headstock decals are primarily applied by scammers trying to sell fake guitars, and if there’s ever a chance you’ll be selling your instrument, websites may take down your posting, delivery services may refuse to ship your instrument, and potential buyers may hate you for selling a “fake”.

Having said that, applying a custom decal with your own logo to the headstock — even if it’s a brand-name neck — doesn’t have the same legal and ethical problems, and it’s pretty cool to play a guitar that has your name on the headstock.

Broadly, visual mods can be divided into two distinct categories: “flat” things where the primary way to modify them is through changing their outline or surface colors or patterns, and “three-dimensional” objects where it’s possible to replace them with something of an entirely different shape.

Things You Can Paint

Throughout this book, I try to stay away from talking about painting things on your own, but parts in this category are simple enough where you can usually get away with just giving them a couple coats of spray paint, and may not even need to sand down or polish the finish.

If you want to do decorate your “flat” hardware with some sick patterns, stickers are the obvious solution, but you may also want to draw something freehand. In that case, I suggest looking into acrylic paint pens.

Acrylic paint pens.

Acrylic paint pens.

These are just like normal marker pens, except they use acrylic paint — the same kind that your guitar finish may use! The result is waterproof and very durable, and if you pop a coat of clearcoat over it, will be able to stand up to even the hardest playing.

Pickguards

A lot of guitars come with a pickguard.

“Pick guard”?

The name “pickguard” is a bit of a misnomer, actually; the pickguard doesn’t actually guard against the pick scratching the finish.

On acoustic guitars, pickguards serve to protect the wood from the nails or fingerpicks when playing the guitar fingerstyle — when playing with a pick, the pick comes nowhere near to the pickguard.

On electric guitars, even that use for a pickguard is mostly irrelevant. It’s much cheaper and faster to manufacture an instrument if you can route all the control cavities into the top — without any complicated routing or drilling necessary for the cable runs — and a pickguard serves as a plate that hides the routs and allows easy mounting of components. Going a step further, mounting all the electronics to the pickguard enables the manufacturer (or anyone else who works on the guitar later) to solder and mount all the electronics outside of the guitar, and then just screw the complete assembly to the body of the guitar itself with a couple screws. Pickguards can make manufacturing and repairs easier!

…But sometimes — like on a Les Paul — they’re just decorative.

Since a pickguard is generally just a flat sheet of plastic (rarely, metal) cut into a shape, it’s very easy to paint or make your own.

A custom pickguard on a

Strat.

A custom pickguard on a

Strat.

Custom pickguards can be found all over the Internet easily for common models of guitars; if your guitar is more unique or doesn’t normally have a pickguard, you can buy sheets of pickguard material and easily trace and cut your own, custom pickguard. A bit of sanding and it will look stunning.

One thing to bear in mind when buying replacement pickguards is that screw placement is… all over the place, generally. Sometimes the screw holes will match what you have, but generally you should not rely on that being true, and you may need to drill some new holes in your pickguard or guitar — or affix it with double-sided tape instead; that works too.

Pickup covers

An uncovered single-coil

guitar pickup.

An uncovered single-coil

guitar pickup.

Pickups generally come with plastic or metal covers that protect the fragile coils from damage, but some (especially humbuckers) eschew covers and just use some tape wrapped around the coils.

It’s sometimes possible to remove covers from pickups that have them on — the exact process may be difficult and is outside the scope of this book.

If you have a pickup without a cover — whether because that’s the way it shipped from the factory, or because you removed the covers it came with — congratulations, you have a wonderful opportunity for a striking visual mod!

Plastic covers for common pickup form factors can easily be found in a variety of different colors, and they’re trivial to spray-paint if the existing selection doesn’t satisfy you.

Because the pickups are so central to the whole look of an instrument, putting some striking covers on can make a dramatic impact on how your instrument looks — they can provide a lot of contrast and visual interest, or offer a splash of color amid a mostly monochrome design.

If plastic pickup covers are not to your liking, there are also metal pickup covers that come in various shades of chrome, nickel, black, and gold. They come in a couple different varieties — “open” covers, which only cover the sides of a pickup, leaving the top open (to minimize the impact on tone that I’ll address in the next paragraph), covers with exposed pole pieces (the kind you might see on a classic Les Paul), and fully-closed covers (typical for active and “modern” pickups).

There’s a catch here, though — metal pickup covers can have a non-negligible impact on tone. The exact specifics are slightly out-of-scope for this book, so I will direct you instead to this stellar analysis by Alex Kenis.

The takeaway, overall, is that the material, thickness, and distance of a pickup cover from the poles can influence the noise level and sound of a pickup quite a bit — cheap and thick brass and steel pickup covers lying very close to the pole pieces dull high frequencies quite a bit but offer a significant level of noise shielding, whereas higher-quality thin nickel silver covers spaced out from the pole pieces don’t reduce noise as well but will also not impact tone nearly as much.

When using metal pickup covers, you should attach them to the pickup by soldering them onto the pickup’s metal base plate, or running a short grounding wire from a grounded point to the cover to shield the pickup from electromagnetic interference.

Metal pickup covers have one advantage over plastic ones when it comes to visual mods — you can pull off a really sick “etched” look by masking off a pattern with some tape and then carefully scratching the pickup cover within the outlines with a knife or something similar. You could probably take them to a local laser-etching place and ask for a custom laser-engraved pattern, too; the possibilities are endless.

On pickup pole piece spacing

Not all pickups are created equal. Take humbuckers, for example — although they look very similar, there are actually two equally common types of humbucker, differing in pole spacing; more if we go into details and extra strings, but we’ll talk about that in the chapter on pickups.

Gibson-style bridges have a narrower string spacing than Fender-style bridges. While it makes little difference for humbuckers in neck position, the difference closer to the bridge is significant enough where you’ll find two different designs, depending on the style of bridge your guitar has.

“Standard” or “G-style” humbuckers are the ones you’ll find in Gibson-style guitars. They have a spacing of somewhere between 49-50 mm between the centers of the outermost pole pieces.

On Fender guitars and ones with Fender-style vibrato systems, the string spacing at the bridge is wider than on Gibson designs, which in turn implies the pickups themselves are wider and have wider pole spacing. These are referred to as “trembuckers” or “F-style” humbuckers. The string spacing on these is somewhere between 51-52 mm.

This issue gets even more complicated when combined with the fact that Gibson have recently started moving towards wider pole spacing, with some modern Gibson pickups being as wide as 52 mm in the bridge position.

Similarly to humbuckers, single-coil pickups vary wildly in pole-piece spacing as well. Some Stratocaster sets can have as much as 4 mm of difference in the pole spacing of the neck and bridge pickups!

When shopping for pickup covers with exposed pole pieces, measure the pickup you’re going to be putting the cover on, and make sure the pole spacing matches!

Minor Hardware

There’s a lot of other minor hardware on your guitar, and the good news is: the more standard your guitar is (i.e. the closer it is to e.g. the standard Stratocaster formula), the more likely it is you’ll find a drop-in replacement!

Pickup Rings

There are two ways to mount a humbucker — directly to the body, or to a pickup ring which decouples height adjustment and mounting force. Pickup rings generally come in a variety of different sizes, differing in height and profile. Guitars like the Les Paul, with a significant neck angle and a bridge that sits at quite some height above the body will use pickup rings with an arched bottom surface — to match the contour of the body — and an angled top surface — to match the angle of the neck — where the bridge pickup ring will be significantly taller than the neck pickup ring. On the other extreme, guitars with low bridges and a neck that’s parallel to the body will generally use very thin and flat pickup rings. Make sure to inspect and measure your pickup rings before buying replacements.

Other sizes of pickup — trembuckers and mini-humbuckers, and even some P90s — may also mount to pickup rings, but they’re harder to find replacements for.

You can find pickup rings made of metal or plastic in a variety of different colors and designs — even clear acrylic ones! They’re trivial to replace, and a set of eye-catching pickup rings can add a lot of flair to an instrument.

A Triple Shot, in default configuration, allows you to achieve four different tones out of a single humbucker — the two coils connected in series, parallel, the neck-side coil solo, or the bridge-side coil solo. With two Triple Shots and two humbuckers, that’s a four tones out of the neck pickup, four tones out of the bridge pickup, and \(4\times4=16\) tones out of both, for a whopping total of 24 different tones!

The downside is — Triple Shots are really expensive. Frankly, obscenely so, but that comes down to the lack of competition — they’re the only such product on the market, as far as I know. If you have too much money and want the ultimate flexibility out of your guitar without sacrificing aesthetics, they might be the choice for you.

Control Plates

I’m going to cheat a little bit in this section and talk about two very different pieces of hardware.

The first is toggle switch plates. You know those little chips you get under a Les Paul-style toggle switch that say “RHYTHM” and “TREBLE”? You can easily find places that will make those with custom text, or even with elaborate metal designs, like skulls and stars. A custom toggle switch plate is another fantastic way to add a small visual accent to your instrument. These are also absolutely trivial to install, and pretty cheap.

Then there’s control plates. These are not particularly common, but feature prominently on e.g. Jazz Basses and Telecasters. They’re the metal plates the electronics are attached to for shielding and ease of assembly.

As with most metal hardware, you can generally find them at least in the standard colors of nickel, chrome, gold, and black. There’s a significantly wider selection of Tele control plates compared to bass ones, so you might also find those made out of different materials, like wood. Both variants exist with custom engraving on them, as pictured.

The Tele Switch Conundrum

The Telecaster control plate has a pretty famous minor design flaw — it puts the volume knob extremely close to the pickup selector, so that with the bridge pickup selected, it’s difficult to adjust the volume without bumping the pickup selector or get a solid grip on the pickup selector without bumping the volume knob.

For that reason, fiddling with the control plate itself is one of the most common mods done to Telecasters.

A Telecaster with a reversed control plate.

Players who strongly favor the bridge pickup or want easier access to their volume knob will often reverse the control plate entirely — it’s an easy $0 mod that just requires flipping the existing control plate and rewiring the controls “in reverse”. This allows very easy access to the volume or tone knob and stops the switch from interfering with the knobs when in the bridge position.

A variety of Telecaster control plate styles.

For those who want to put more space between the knobs and the switch entirely, there exist a variety of Telecaster control plates that change the positioning of the potentiometer and switch holes to adjust the spacing of the individual controls on the instrument. A particularly common variant has the switch mounted at an angle, rather than in-line with the knobs; there also exist control plates that have cutouts for Les Paul-style toggle switches, rather than the stock blade switch, or ones that just move the knobs closer together.

If you have a Telecaster, consider getting yourself a control plate with a non-standard layout — they’re cheap, not particularly visually intrusive, easy to install, and they can make a big difference to how your instrument feels.

Neck Plates, Truss Rod Covers, and Other Minor Things

There’s a lot of other minor hardware on a guitar — bolt-on designs often have neck plates that prevent the screws from damaging the woods (although more modern instruments often use per-screw ferrules), a lot of guitars with tiltback headstocks have the truss rod covered by a little plastic cover, and if your guitar has a rear-routed control cavity (like a Les Paul), its covers can also often be replaced.

I’ll run through these with examples very quick.

Neck Plates

An engraved neck

plate from Gotoh.

An engraved neck

plate from Gotoh.

Neck plates, most commonly found on Fender-style bolt-on designs, serve to distribute the force from the neck screws — to avoid damaging the wood or finish of the instrument. They’re just a flat metal plate with (usually) four screw holes, so they’re very cheap and easily available with a variety of custom designs and engravings.

Control Cavity Covers

A clear

control cavity cover for a Les Paul.

A clear

control cavity cover for a Les Paul.

Guitars with rear-routed control cavities generally have them covered by a plastic (rarely, wooden) control cavity cover plate. Since it’s yet another flat, untextured piece of plastic, it’s a prime candidate for stickerbombing or replacing with a different-colored one, much like a pickguard! They’re also pretty easy to make yourself with a hand saw, some sandpaper, and time. I particularly like clear acrylic control cavity covers that let you see the electronics inside. Replacement Strat tremolo covers and Les Paul control cavity covers are easily available in a million different variants.

Truss Rod Covers

A custom metal truss

rod cover.

A custom metal truss

rod cover.

On guitars with tiltback headstocks, the truss rod — if accessible at the headstock — is usually hidden under a plastic cover. This also happens to be one of the most commonly misplaced parts of a guitar — lots of secondhand guitars are missing this little piece of plastic, and a lot of players (yours truly included) prefer to keep it permanently off, since it does nothing but make setup more of a hassle. If you do, however, choose to keep your truss rod cover on, you may want to get some fun custom text on it, or maybe an entirely custom-made metal one. There are a lot of options, especially if you have a Les Paul or are willing to drill a couple tiny holes in your headstock.

An Ibanez truss rod

cover.

An Ibanez truss rod

cover.

If you want the best of both worlds — to keep your truss rod covered, yet not have to unscrew the cover for adjustment — Ibanez, in their never-ending quest to overengineer every single part of a guitar, have truss rod covers that have a little plastic “door” that swings out to the side and a channel cut in-line with the truss rod to allow you to get an adjustment tool in there without unscrewing the pickup cover. Neat!

Things You Can Make

Everything we’ve talked about so far is mostly “flat” stuff where most of the visual customization options available to you will be changing the part to one of a different color or pattern. It’s time to talk about things that vary in shape.

Knobs

Okay, let’s get the laughter out of the way first, ha ha, there’s going to be lots of unfortunate phrasing in this section. It was unavoidable.

Knobs. My favorite thing to swap out, believe it or not. The knobs on a guitar can be anything from a purely utilitarian piece of plastic to a beautiful central piece of the composition that is your instrument. Every knob is a design statement.

How To Avoid Getting Shafted By Shafts

Before we talk about the different styles of knobs, let’s talk about compatibility first. As far as knobs are concerned, there are two types of potentiometers (there are more, but only this distinction matters for the purpose of what knobs will fit): split shaft and solid shaft.

Split shaft potentiometers have — you guessed it — a split shaft. The shaft is knurled to stop the knob from spinning freely, and split down the middle to allow you to adjust the pressure it exerts on the inner surface of the knob by slightly forcing the two halves apart with e.g. a flat-blade screwdriver. These are used on virtually all modern guitars.

Split shaft pot shafts have an outer diameter of 6 mm or 0.235“.

Cryptid pots

I’m told there are two different types of split shaft pots that differ by the density of the knurling, but… I’ve never seen them actually used. In my experience, split shaft knobs fit on split shaft pots; if there are distinct types of split shaft pots, then the “other” kind is extremely obscure and I have never come across it or knobs made for it.

To install a knob with a set screw on a split shaft pot, align the set screw with the split.

A solid shaft potentiometer’s shaft is a completely smooth, solid cylinder. Since they don’t have knurling or a way to compress and exert pressure that would hold a knob in place, solid shaft potentiometers rely instead on a small set screw in the knob itself that presses up against the shaft.

The outer diameter of a solid shaft potentiometer’s shaft is about 6.35 mm, or 1/4“. This means they will not fit most knobs.

Solid shaft potentiometers are used pretty much only in vintage guitars — primarily on Telecasters.

Before shopping for knobs, make sure to check what style of potentiometer your guitar is using, and plan accordingly. Most knobs will fit split shafts; if you have a solid shaft, double-check that the description of the knob specifies a 1/4“ inner diameter.

Classic Knob Styles

There are many, many styles of knobs in the guitar world. Let’s start by looking at the classics.

-

Strat-style

If there is a classic knob design, this is it. Legible, utilitarian, available in a plethora of colors — I never quite figured out which way the numbers are supposed to go. These have a certain air of lightness and yet ruggedness to them — they will feel right at home on a sleek yet classic-influenced guitar — just like a Strat!

-

Gibson “Top Hat”

These are the knobs most Les Pauls and similar designs come with. They have a solid colored plastic base plate with numbers, while the top of the knob is made of a different, translucent plastic. Their shape is similar to the Strat knobs’, but they lack any knurling. You can also get them with metal inserts on the top with labels describing the knob functions.

-

Speed knobs

Somewhere in the 80s (I think) Gibson introduced a new knob design that wasn’t stepped midway through to a wide cone, like the classic top hats, but rather had completely straight walls. For whatever reason, these are called speed knobs. They used to be a favorite of many, many guitar manufacturers, until metal dome knobs became fashionable in recent years.

-

Telecaster/Precision Bass

These are classy as hell. Heavy, solid knurled metal, these were made for the 1/4“ solid shaft potentiometers — but you can easily find copies for split shafts. There are two styles of these — the more vintage flat-tops, and the more modern “dome” variant.

The set screw makes them uniquely easy to adjust or replace even on split-shaft pots, because rather than try to pull the knob off with force all you need to do is loosen one screw. They also feel great — the knurling provides lots of grip, and a lot of the knobs of this style feel very substantial and high-quality due to the material choices — solid brass is popular, as is aluminium.

The Fender replacement tele knobs are… questionable. They are horrifically overpriced, and the “Tele/Precision Bass Knurled Knobs” are garbage quality as well — they’re probably cast zinc or something similarly cheap. The “Pure Vintage” ‘52, ‘58, and ‘60s knobs Fender stocks are much higher quality — and made from proper brass and aluminium — but cost over $20, which is slightly ridiculous for a pair of knobs.

Psst, Allparts makes very nice replacement tele knobs for half the price Fender wants.

-

Jazz Bass

These are quite funky and look more like amp or pedal knobs than like typical guitar knobs — in fact, MXR uses these on a lot of their pedals.

- “Witch Hats” Not only do these have the sickest name of any knob style, they also have tremendous vibes. They were used by both Gibson (ES-335s, SGs) and Fender (Jazzmaster, Tele Deluxe) — they are minor variations between the two styles, and you can find “witch hat” knobs with or without a set screw, but they all look broadly similar — a narrow knurled shaft with a silver plate at the top and a flatter, wide base.

-

PRS “Lampshade”

These are quite similar to Gibson speed knobs but have a polygonal, rather than completely round, profile and flare out slightly towards the bottom. I think they look sick. Especially the clear ones look stunning on a guitar with e.g. a flat black and white color scheme, they look almost like crystal or glass.

Unique and Novelty Knobs

Of course, the classic knobs are not the only flavor of knob out there. Etsy in particular has tons of unique knobs, and I highly recommend browsing through all the varieties out there and picking something that will look great on your guitar. Here are some of my favorites to give you an idea of the variety of knobs you could put on your guitar:

-

Lucky Dog Dragonback II (Etsy)

Self-describing as “the most aggressively knurled knob on the market”, these are machined out of solid aluminium and have a particularly heavy industrial look to them. Excellent.

-

Fancy-topped knobs

Feel like solid brass isn’t premium enough for you? How about solid brass with a mother-of-pearl top? There are plenty of these in all shapes and sizes. Similarly, you can find ones topped with abalone, faux-tortoiseshell, faux-gemstones (and probably real ones too!), and a variety of other eye-catching materials. Want a geeky Star Trek-themed guitar? How about some Starfleet insignia-topped knobs?

The possibilities are endless.

-

Wooden knobs

If you want to add a “handmade” flavor to your guitar — especially if it has a natural finish — it’s hard to beat wooden knobs. These can be found in a million billion designs and you’re certain to find one that will fit your instrument.

-

Funky knob shapes

Want a knob that looks like a star? A D20? A shotgun shell? How about a skull? Anything you can drill a hole in, someone probably makes guitar knobs out of. Thingiverse also has plenty of these, if you have access to a 3D printer.

-

Patterned knobs

A particularly common trend in knob design is to have a metal knob with some kind of pattern or symbol engraved on the top. You can find a wide variety of these — with vines, celtic weaves, pentagrams, old US coins pressed into the top, etc etc.

Summary

The knobs are the second most-frequently touched part of your instrument, after the neck.

If you want to give your guitar that extra bit of premium feel, try swapping them out for heavy, solid metal knobs. If you want a more industrial vibe, try witch hats or any of the rougher, beefier metal knobs. If you want something high-class and shiny, try PRS knobs or ones with premium material inlays.

Fox’s Gear: Screw-fit Dome Knobs

Knobs are one of the first things I replace on my instruments, because they’re cheap and taking off press-in (as opposed to screw-tightened) knobs is an absolute pain in the ass, so I’d rather avoid doing it more than once — especially if I’m going to ever mess with the electronics.

Metal knobs also, subjectively, for me, make an instrument feel a lot more premium than plastic ones, so I usually get rid of plastic knobs and replace them with brass dome knobs held on by set screws.

Experiment! Knobs are inexpensive and easy to swap out, and they can add a lot of flavor to an instrument. Well-selected knobs really tie together a guitar visually and can make it feel more personal and consciously designed rather than mass-produced on an assembly line.

Switch tips

We’ve talked about switches in-depth in the chapter on wiring — this is about switch tips.

Most “big” guitar switches (the kind you find used as pickup selectors) come with (usually plastic) removable switch tips.

The toggle switch on

a Les Paul, with a cream plastic switch tip.

The toggle switch on

a Les Paul, with a cream plastic switch tip.

Switch tips come in almost as wide a variety as knobs. The blade-style switch tips are interchangeable, for toggle switches you’ll have to find one made specifically for your switch (although the Les Paul shaft is pretty standard).

Much like we did with knobs, you’re going to have the most luck looking for novelty switch tips on sites like Etsy and Ebay; some show up on Amazon and Aliexpress, and sometimes you can find interesting switch tips in stock at usual guitar hardware retailers or sold by individual manufacturers.

The interesting thing about switch tips — and knobs, now that I think about it — is that basically anything you can drill a hole in (if you have a toggle switch) or cut a slot in (if you have a blade switch) can be a switch tip. Go wild — hell, make switch tips out of old Hot Wheels cars if you so desire. With a drill or a dremel and maybe some hot glue, anything you want can be a switch tip.

Plastic switch tips can also be easily purchased in basically any color you’d like, and are very easy to paint yourself — just give it a couple quick layers of spray paint and you might not even need to sand it.

The Electrical Systems

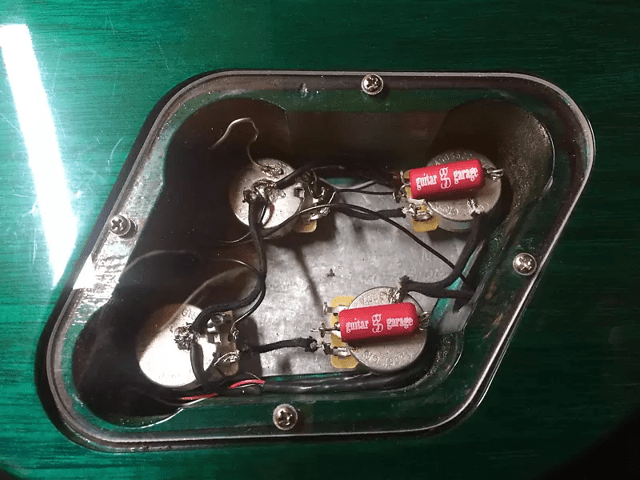

Oh boy, it’s time to talk about the elephant in the control cavity.

The electrical systems in guitars are much, much simpler than most people think they are, and a basic understanding of how they work is crucial to figuring out your own wiring and switching setups, and often for making basic repairs and modifications.

Electronic or electrical?

I’m deliberately trying to avoid using the term “electronics” because the distinction between electric and electronic is a bit blurry and I, frankly, don’t understand it. But there’s probably a reason why it’s an “electric” guitar, but an “electronic” keyboard.

What Makes The Angry Pixies Dance

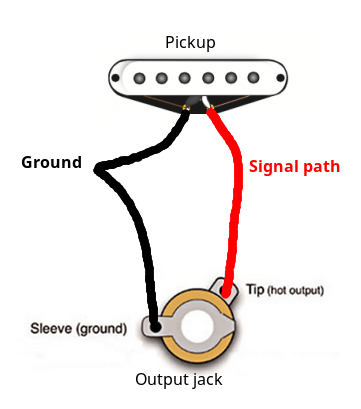

At its core, every guitar wiring setup looks basically like this:

A basic wiring setup for one

pickup, with the ground wire connected to the sleeve of the output jack, and

the hot wire connected to its tip.

A basic wiring setup for one

pickup, with the ground wire connected to the sleeve of the output jack, and

the hot wire connected to its tip.

All the electrically-neutral components are connected together and form the ground, which is the reference point for the output signal of your guitar to be measured against.

You can think of a pickup as an electrical doodad that takes the electrical potential of the ground as an “input”, and “adds” the energy of the vibrating strings to it; our ground wire goes into the pickup, and out comes a wire carrying signal.

Inputs and outputs

Remember this detail, because I’ll be referencing it a lot — the ground is like the “input” of a pickup, and the signal is its “output”.

The wire carrying signal needs to connect to the tip of the output jack, while the ground wire is connected to its sleeve to provide a reference point.

Voltage only makes sense as the difference in electrical potential between two points — you always need two points at different electrical potentials to measure or use voltage in any way! That’s why we need both a ground and a “hot” wire.

That’s the basic principle.

Inventing a Volume Knob

A diagram of how a

potentiometer is built.

A diagram of how a

potentiometer is built.

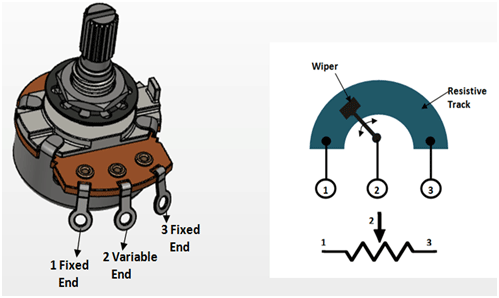

Your guitar probably has one or more potentiometers to control the volume, tone, and possibly other aspects of the instrument’s sound. A potentiometer is very simple: it controls a wiper that glides along a conductive, resistive track between two points.

The resistance between the two end points of the track is equal to the potentiometer’s rating. The middle contact on a potentiometer connects directly to the wiper. This means that:

-

At full counterclockwise rotation:

The wiper connects contacts 1 and 2 directly (the resistance between them is 0). The resistance between contact 1|2 and contact 3 is equal to the potentiometer’s rating (e.g. 500 kΩ if the potentiometer is rated at 500k)

-

At full clockwise rotation:

The wiper connects contacts 2 and 3 directly (the resistance between them is 0). The resistance between contact 1 and contact 2|3 is equal to the potentiometer’s rating (e.g. 500 kΩ if the potentiometer is rated at 500k)

-

Between those extreme points, the resistances between contacts 1-2 and 2–3 are proportional to the potentiometer’s travel, i.e. on a 500k pot set to exactly 50%, there would be 250 kΩ between contacts 1–2 and 250 kΩ between contacts 2–3.

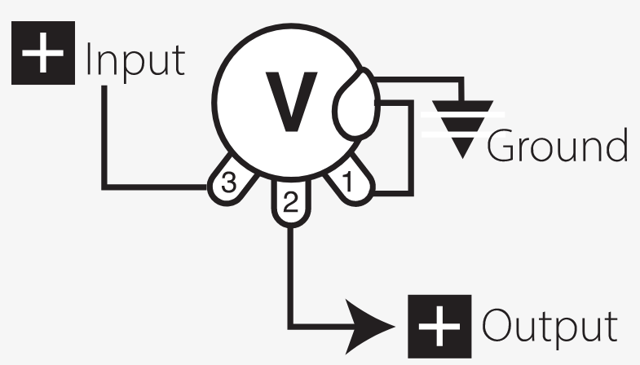

This is enough for us to now invent a volume knob.

We know that:

- At 100% (full clockwise), all of the signal inside the “hot” wire should reach the output.

- At 0% (full counterclockwise), none of the signal from the hot wire should reach the output.

This would hint that we need the output and the hot wire to be connected to contacts 2 and 3, because at full clockwise rotation those are the ones connected directly — i.e. all of the signal on contact 2 goes into contact 3, and vice versa.

The thing about electricity, however is that it tries very hard to get to ground, and so if we wired the volume pot like this:

A potentiometer with the

hot wire connected to the middle pad, the output connected to one of the outer

pads, and the other output pad left unconnected to anything.

A potentiometer with the

hot wire connected to the middle pad, the output connected to one of the outer

pads, and the other output pad left unconnected to anything.

The signal would still reach the output, even at full counterclockwise rotation. The potentiometer adds resistance, but it never disconnects the contacts entirely. Also, leaving the output unconnected to either signal or ground makes it susceptible to noise. We can solve both of these problems by grounding the output at full counterclockwise rotation.

Our revised constraints are:

- At full clockwise rotation, the signal wire must be connected directly to the output

- At full clockwise rotation, contacts 2 and 3 are connected directly

- At full counterclockwise rotation, the output must be connected directly to ground

- At full counterclockwise rotation, contacts 1 and 2 are connected directly

It’s easy to see that the output must be connected to contact 2, contact 1 being ground and contact 3 being signal:

Input connected to one of

the outer pads of a potentiometer, with the middle pad connected to the output,

and the other outer pad grounded.

Input connected to one of

the outer pads of a potentiometer, with the middle pad connected to the output,

and the other outer pad grounded.

“Volume independent” wiring

The volume pot wiring we just invented presents a certain problem particularly prevalent in Gibson guitars, which often use it; if your guitar has multiple pickups (and multiple volume pots), turning the volume down on any one of them shorts the output to ground, and thus silences all pickups! If you’re in that situation and find it a concern, just swap the input and output, so that the input (signal), rather than the entire output, is shorted to ground at 0% volume.

Inventing a Tone Knob

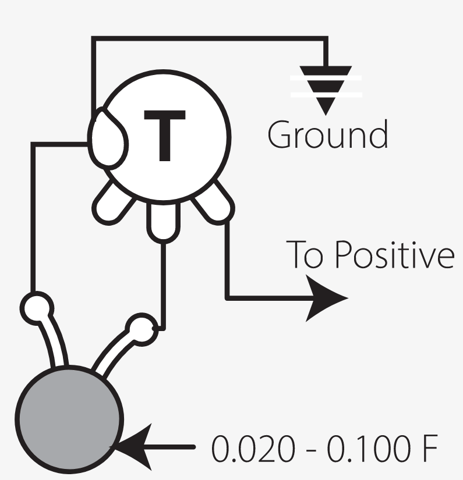

Oh no, I have a Telecaster and the bridge pickup is so bright it sounds like it’s Trotskying my head! Fear not, let’s invent a treble roll-off potentiometer. We’ll need a new component: the capacitor.

For our purposes, all that matters is that a capacitor blocks low frequencies and passes through high frequencies. The cutoff frequency depends on the capacitor rating — the higher the rating, the more frequencies it lets through.

Knowing this, we can infer that we can use a capacitor connected to ground to selectively ground high frequencies (effectively removing them from the signal) while leaving low frequencies unaffected.

There are lots of ways to wire up a tone pot, so I will skip ahead to just showing you a working diagram.

One of the many possible ways

to wire a tone pot, by putting a capacitor between the middle lug of a

potentiometer and ground, and soldering the hot wire to one of the outer lugs.

One of the many possible ways

to wire a tone pot, by putting a capacitor between the middle lug of a

potentiometer and ground, and soldering the hot wire to one of the outer lugs.

Connecting a pot wired like this to your signal wire will let you control the treble roll-off. Let’s analyze why it works:

- At one end of the travel, the capacitor is connected directly to the positive (signal) wire, so high frequencies pass unimpeded through it into ground. This removes the maximum amount of high frequencies from the signal.

- At the other end of the travel, the full resistive track of the potentiometer is between the positive wire and the capacitor, so the signal will prefer to take a path of less resistance, and will not go down the capacitor — i.e. the signal will be unaffected.

Switching Things Up

It’s time to invent switches!

There are many different types of switches used in guitars:

- Les Paul-style three-position toggle switches:

- Telecaster-style three-position blade switches:

You can also find four-position versions of these, for the (wonderful) four-position Tele mod — which adds a position with both pickups in series for a massive sound.

-

Stratocaster-style five-position blade switches:

These are actually interchangeable with Tele-style three and four-position switches!

There are also a number of specialized types of switches that allow for expanded switching options:

-

Push-pull pots, where you can pull up on the knob to toggle between two states.

These are generally DPDT, meaning they have six contacts — one position connects each of the middle contacts with their corresponding upper ones, and the other connects them to the ones on the bottom.

- Mini toggle switches that come in a ton of different variations (SPST,

SPDT, DPDT, 3PDT…)

SPST, DPDT?

Those funky “_P_T” acronyms stand for “_ Pole, _ Throw”. The number of “poles” a switch describes the number of independent circuits it can control; the number of “throws” indicates the number of internal contacts (you can think of them as “connections”) each circuit has. For example, an SPST (Single Pole, Single Throw) switch just has two contacts which are connected in one state and disconnected in the other.

A DPDT (Double Pole, Double Throw) switch has two circuits (double pole), each with three contacts (two connections per circuit, i.e. double throw) — in one position the middle contact of each circuit is connected to the top one, in the other position it’s connected to the bottom one.

- Rotary switches, which work similarly to normal three, four, five, six- position switches but can replace e.g. a volume or tone knob.

- The Super Switch — a five-position switch with four poles that can replace a Tele or Strat-style blade switch.

- Freeway switches, which add a second “side” to a normal 3- or 5-position switch, turning them into a 6 or 10 position switch respectively.

- And even arcade button-style momentary switches, famously used by Buckethead as a killswitch (a momentary switch wired to mute the signal from the pickups as long as it’s held down).

- They’re not switches, but I’d like to also mention the existence of concentric (stacked, dual) potentiometers — they’re basically two independent potentiometers constructed so that one shaft is contained within another and sticks out above it; these let you control two different things independently using just one hole for a potentiometer!

A note about basses — blend pots

It’s quite uncommon to find guitar-style pickup selectors on a bass.

Most basses just use individual volumes for each pickup, or a master volume combined with a blend pot (also called a balance or pan pot, or more technically a dual gang potentiometer).

A blend pot is pretty much just two stacked volume potentiometers controlled by a single knob. They’re usually wired so that one of the banks works as a normal volume control for the neck pickup, and the other bank works as a volume control for the bridge pickup wired by reverse — i.e. turning the knob increases the volume of one pickup while simultaneously decreasing the volume of the other.

> A pan pot.

Inventing a Telecaster Pickup Selector

Let’s start by examining the simple case of wiring up a Telecaster so that we can have switching between the pickups.

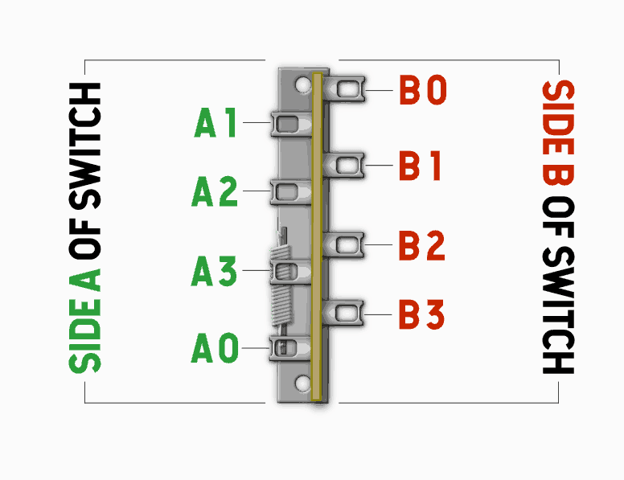

Although there are so many types of guitar switches, virtually all of them work on the same principle: there are one or more “sides”, and each side has a common contact, usually marked C or 0, which connects to a different “non-common” contact for each position (it’s called “common” because it’s part of the switched circuit in every position of the switch). Looking at the bottom of a Telecaster switch:

A diagram of the

contacts on a three-position Telecaster blade switch.

A diagram of the

contacts on a three-position Telecaster blade switch.

In position 1, contact B0 is connected to B1, and A0 is connected to A1. All other contacts remain unconnected.

In position 2, contact B0 is connected to B2, and A0 is connected to A2. All other contacts remain unconnected.

In position 3, contact B0 is connected to B3, and A0 is connected to A3. All other contacts remain unconnected.

Simple enough!

Let’s figure out how to wire up a Tele switch so that we get:

- Only the bridge pickup in position 1

- Both pickups in parallel in position 2

- Only the neck pickup in position 3

Series and parallel

Remember how I talked about voltage being a difference in electric potential, and about thinking of pickups as “adding” the energy of the vibrating strings to their reference (ground)?

You can connect multiple pickups in series or in parallel.

Parallel is the obvious one — you just connect their outputs together. That way, both signals reach the output directly. You can think of the result as the average of the two signals; it’s a pretty transparent sound that preserves the dynamics of each pickup and matches their individual sounds in volume.

Series wiring is a bit spicy — you take the output of your first pickup and run it directly into the input (the “ground” wire) of your second pickup. That way, the signal will be the sum of the two pickups’ outputs.

With series wiring, the electricity has to travel through both pickups, which does some funky things to the sound; overall, this means that series wiring is beefier, darker, and louder than parallel wiring.

To figure this out, let’s do a similar logic puzzle to what we did with to invent a volume knob:

- To connect the bridge pickup to the output in position 1, the bridge pickup and output must be connected to pads A0 and A1 (in any order), or B0 and B1 (in any order).

- To connect both pickups to the output in position 2, the bridge pickup, neck pickup, and output must be connected to some of the pads A0, A2, B0, B2.

- To connect the neck pickup to the output in position 3, the neck pickup and output must be connected to pads A0 and A3 (in any order), or B0 and B1 (in any order).

There’s not that much difference between wiring and Sudoku, really.

Let’s solve this by… picking pads at random! I’ll just start from the top and use the first appropriate pad for each connection.

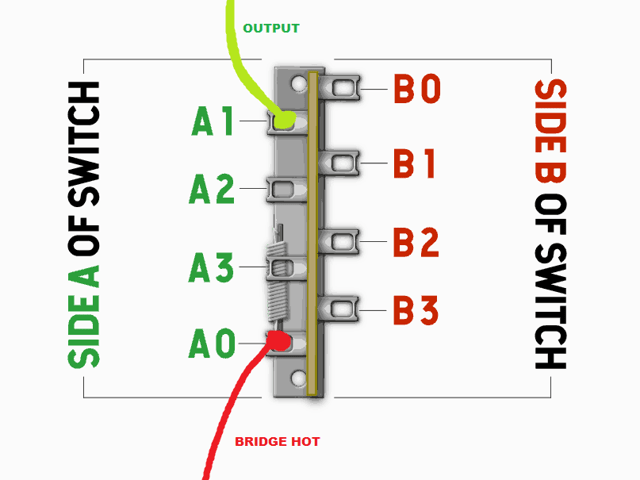

First on our list is the hot wire from the bridge pickup, and we know by constraint a. that it can be connected to A0, A1, B0, or B1. Let’s connect it to A0. By constraint a., we also know that if the bridge pickup is connected to A0, A1 must be connected to the output:

We connect the output

to pad A1, and the bridge hot to the switch’s side A common pad.

We connect the output

to pad A1, and the bridge hot to the switch’s side A common pad.

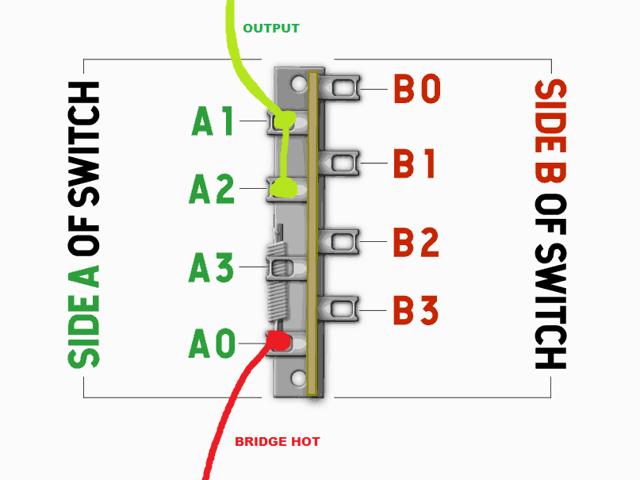

Continuing, we know that the bridge pickup should also be connected to the output in position 2, which connects pads A0-A2 and B0-B2. Since A0 already has signal from the bridge, we can just connect A2 to the output to ensure the bridge pickup remains active both in position 1 and position 2.

Connecting pad A2 to

A1 as well ensures that the bridge pickup remains active in both position 1

and 2.

Connecting pad A2 to

A1 as well ensures that the bridge pickup remains active in both position 1

and 2.

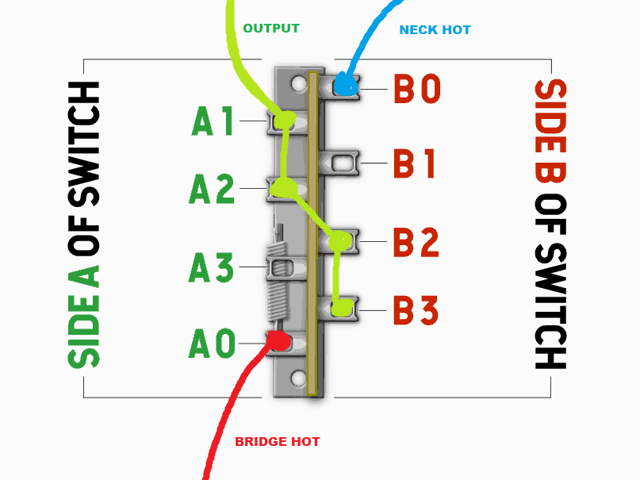

This leaves us with the neck pickup. We know by constraint b. that the pads we can use in position 2 are A0, A2, B0, B2, but we’ve already used A0 and A2 for other things, so let’s just pick the first remaining pad and connect the hot wire from the neck pickup to B0. For the neck pickup to be active in position 2 and 3, that means B2 and B3 should be connected to the output:

All that’s

left is to also connect pads B2 and B3 to the output, connect the neck pickup

to the common pad of side B, and we’re done!

All that’s

left is to also connect pads B2 and B3 to the output, connect the neck pickup

to the common pad of side B, and we’re done!

Aaand… Our switch is all wired up and ready to go into the guitar! Let’s double-check:

-

In position 1:

A0(bridge hot) is connected toA1(output), so we get sound from the bridge pickup.B0(neck hot) is connected toB1, which isn’t connected anywhere, so we don’t get sound from the neck pickup. -

In position 2:

A0(bridge hot) is connected toA2, which has a wire running toA1(output), so we get sound from the bridge pickup.B0(neck hot) is connected toB2, which has a wire running toA2, which has a wire running toA1(output), so we get sound from the neck pickup. -

In position 3:

A0(bridge hot) is connected toA3, which isn’t connected anywhere, so we don’t get sound from the bridge pickup.B0(neck hot) is connected toB3, which has a wire running throughB2andA2toA1(output), so we get sound from the neck pickup.

Get the confetti ready, we just reinvented a seventy-year old wiring scheme! Great job.

Is there a point to all of this?