Bass Bridges

Since a bass bridge is much beefier and larger than a guitar bridge and because — unlike guitar — the electric bass is pretty much entirely a Fender invention, bass bridges in general offer much greater compatibility and adjustability than guitar bridges.

Let’s start with the most basic of them all.

The Standard Fender Bass Bridge

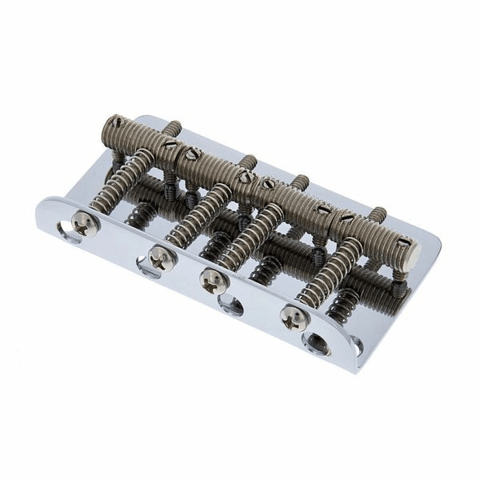

A vintage-style Fender

bass bridge.

A vintage-style Fender

bass bridge.

Twelve screws, a threaded rod cut in three places, and a bent sheet metal plate. This design — used by both the Jazz and Precision basses and a myriad of non-Fender designs — is even less sophisticated than a Telecaster bridge, yet it has remained pretty much unchanged since the 50s.

In its original 1951 iteration, much like the Telecaster, it had two strings per saddle, for a whopping two individually adjustable saddles in total. It soon got revised with individual saddles for every string, and later revised again so that the saddles were smooth, rather than threaded. The basic design remains to this day.

When shopping for bass bridges, double-check the spacing and number of screw holes for the mount — there are both four- and five-screw mount variants, but if the screws match, the bridge is generally a drop-in replacement.

The vintage bridge has a certain shoddiness to it, and some players (myself included) have a strong dislike for it just because of how cheap it looks and feels. Those players quickly found themselves swapping these bridges out in the 70s, when the Badass bridge entered the market.

The Badass Bridge

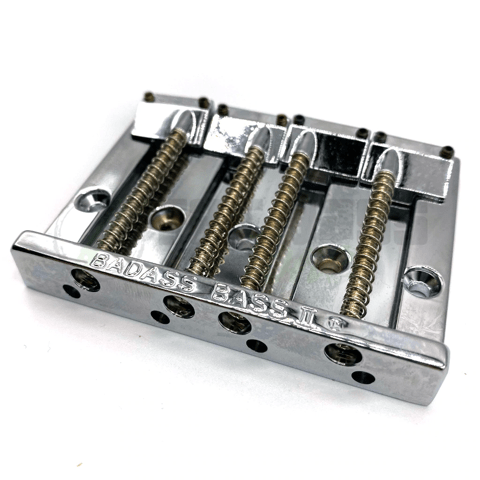

A Badass II bass bridge.

A Badass II bass bridge.

The Badass bridge is, to this day, one of the most common hardware upgrades for guitars and basses, second perhaps only to pickup swaps.

While the Badass is a brand name and a trademark, the design itself has been cloned by virtually every hardware manufacturer and their mom. Even Fender make their own Badass-style bridges, under the name “Hi-Mass”.

The Badass is… not a particularly big improvement over the standard design, actually. It uses a beefier baseplate and saddles that are much more stable, but overall it’s pretty much the same design, just with some geometry tweaked. Nevertheless, it’s a nice and inexpensive drop-in upgrade for most basses.

When I say “inexpensive” I mean it — the Fender Hi-Mass bridges are some of the cheapest bass bridges you can buy. I’ve seen them go for as low as $20 new!

Hipshot Bass Bridges

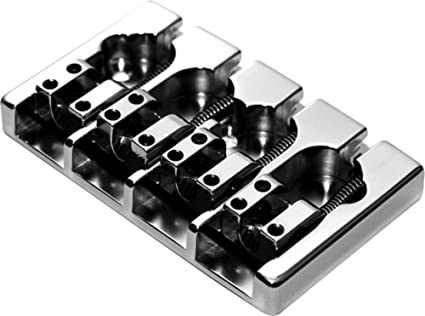

A Hipshot A-Style bridge.

A Hipshot A-Style bridge.

Ah, now we’re getting into the realm of ultra-premium hardware.

Let me get this out of the way first—these are very pricy. I mean “$150 and up” pricy.

Hipshot make a variety of extremely high-quality bass bridges, available with screw-patterns matching all the most common designs — Fender-style, Gibson-style, and even Rickenbacker bridges. They’re machined from heavy aluminium and brass and usually feature very fine adjustment for action, intonation, and even string spacing. On basses with high-end hardware, you’ll find either a Hipshot, or a bespoke bridge more often than anything else.

Other Common Designs

Gibson 3-Point Bridge

These virtually never show up on non-Gibson basses — and there aren’t that many Gibson basses out there — but they’re a pretty good (if a bit quirky) design.

The Gibson 3-point design, rather than being tightly screwed into the body like most other bass bridges, is instead forced by string tension to press against a trio of studs embedded in the body. Much like a Tune-O-Matic tailpiece, it can move freely rearward once string tension is removed.

I had a quick check, and I don’t think anyone other than the ultra-premium manufacturers — Hipshot and Babicz –– makes a retrofit for this design that improves on it in any way, rather than being a direct clone.

Schaller 3D

These are a bit of a wildcard here. They’re not a drop-in replacement for anything, nor do they come preinstalled on a lot of instruments (some Warwicks used to come with Schaller 3D bridges, I don’t know if they still do it). Nevertheless, they are a popular upgrade, and it doesn’t take a lot of effort to fill the old bridge holes and drill some new ones so that you can pop a 3D bridge on your bass.

This design is unique is that it’s available as a guitar bridge as well. These are pretty great bridges — massive, with roller saddles, easy and precise intonation and height adjustments, and even adjustable string spacing.

A word on “Quick Release” bridges

There is one design choice I don’t necessarily agree with that’s particularly prevalent in bass bridges (as opposed to those meant for guitar): “Quick Release”.

Broadly speaking, a “quick release” bridge is one where the strings, rather than being threaded through a hole, are anchored in a slot so that upon releasing the tension on the string it can immediately and easily be popped out of the bridge without having to pull the entire length of the string through a narrow hole.

This design has some very real benefits — it makes destringing your instrument a lot easier and faster, removes the occasional need to clip off the old string (thus rendering it impossible to reuse), and makes it trivial to use the same strings again after taking them off your instrument (repeatedly, perhaps).

All this comes at the minor cost of making stringing up your instrument trickier. Because a quick release bridge relies on the tension of the string to keep it seated, it’s up to you to provide that tension before the string has been properly anchored at the tuner and pulled up to pitch. This makes stringing a bit of a three-hand operation, since you need to, at the same time, guide the string around the tuner (which often requires two hands), maintain a constant pull on it, and keep the ball end anchored in the bridge.

I’m not a fan of that, and I value the quicker stringing of non-quick-release bridges more than the ease of destringing and the ability to reuse strings. Make your own decision about which one seems more attractive to you!